The last few years have been rather tumultuous in UK politics. A far too regular change of prime ministers culminating in recent resignations and even the brief arrest of the former First Minister of Scotland. But the UK is not the only country where politics seems to have gone a little off-piste and the public seems to be more interested in the politicians than the actual politics.

In recent years, The Book Collector published three articles by John R. Payne on how he appraised President Nixon's archive as part of the settlement between him and the then Administration. Putting a value on the Watergate tapes? On Nixon's letter of resignation? This was truly historic stuff. All publishers get the feeling now and then that they have on their hands material that needs to be in the public domain. So James Fleming met up with John and 'Valuing a Presidential Library', now available for all to read online, was the result.

The politically interested can't deny their curiosity concerning anything that tells us a bit more about the politician – the man or woman behind the political façade. What did they really think? Did they agree with their fellow politicians? Do they regret any of their decisions?

Many prominent politicians are publishing their memoirs (some so quickly, they hardly had time to run the country), but most of these are of course written by ghostwriters who are experienced at what should and what shouldn't go into a biography.

So how do you find out about what they really thought? In the past, political scientists would have been able to analyse the personal letters of politicians. What will future academics do, given that most of our correspondence is now via email and WhatsApp? The only hope may be ghostwriters willing to share some of the material they were given access to.

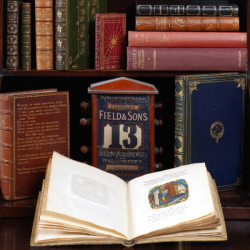

Nicholas Worskett, Bellmans' book specialist, recently came across another way to find out what a politician really thought. Looking through boxes of books that were part of the library of the Earl and Countess of Avon, he spotted a couple of annotations and discovered more about the former Prime Minister Anthony Eden (1897–1977) than he had thought possible: ‘It has been a rare privilege and an education for me to discover more about Anthony Eden through his book collection, and to find so many books with his annotations which are often surprising for their candour, revealing the off-duty, unofficial statesman. Every book tells you something about its owner, but rarely, as here, do they provide a unique and compelling insight into momentous world events. There was a great deal more to Anthony Eden than the elegantly-attired Prime Minister who resigned over the Suez Crisis, which is how people tend to remember him.’

Indeed, he had only been Prime Minister for two years when he resigned in 1957. Although he may not have gone down in history as a particularly successful PM, his political career was exceptional. He went to Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, fought in World War I with distinction, being awarded the Military Cross, and became an MP for Warwick and Leamington in 1923 at the age of 26. From 1935 he held various ministerial positions, including Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs three times, representing the country abroad for over 10 years in total. He was also the first PM who was divorced, but married by then to Clarissa Churchill-Spencer (1920–2021), who later became a well-known memoirist.

The auction of Eden's Library on the 13th July includes a wide range of books, but one of the most interesting ones for the politically-minded is Munich. Prologue to Tragedy by John W. Wheeler-Bennett (1902–75), published in 1948. It is a first edition presentation copy inscribed, ‘For Anthony Eden, with warmest best wishes and very many thanks, John W. Wheeler-Bennett, May, 1948.’ What makes it fascinating are the copious annotations and highlighted passages, unusually for Eden in ink, not pencil, principally to the first half of the book, often in outspoken and personal terms – for example, on p. 15 (commenting on Sir Nevile Henderson, British Ambassador to Germany from 1937 to 1939), ‘Disastrous man and disloyal to me. Note his conversation with Buchanan [?] in our Embassy Berlin day 1 ... He proclaimed his delight & added now we shall be able to make friends with Germany;’ on p. 39 (on Neville Chamberlain) ‘Later he did this for Poland & Rumania. [Sir John] Simon took his line against me in debate after Hitler had entered Prague [etc];’ on p. 40 (on Chamberlain) Eden writes, simply, ‘Ass!’; and on pp. 44–45 (on Chamberlain) he writes, in an extensive note that fills two thirds of a largely blank page, ‘If he had really been concerned he should have presided over our rearmament [?] – as I frequently urged him to do in vain ... A further difficulty about rearmament was that neither N.C. nor [Sir Thomas] Inskip knew the simplest rudiments of military matters.’ The lively language employed in some of these personal notes, perhaps intended as aides-memoires or scribbled in the heat of the moment, tends to counter the more familiar characterisation of Eden as a rather distant, formal and patrician figure.

All this leads me to wonder what we may find in the libraries of Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin.