At 60 the Lilly Library is one of the younger, important libraries in the United States.The Book Collector has an especially strong connection with it as it has been home to our founder Ian Fleming's book collection since 1970.

This week's podcast, read by English actor Rupert Vansittart, is part of our Contemporary Collectors series. In it, David Randall wrote about Josiah Kirby Lilly, who made a fortune from pharmaceuticals and then spent much of it on buying books. It was published in our Autumn 1957 issue (page 263). (It was Randall who negotiated with Ann, Ian’s formidable widow, the purchase of Ian Fleming's library.)

J. K. Lilly was a collector most of his life (he died in 1966). His collections included books and manuscripts, works of art, coins (most of them now in the Smithsonian), stamps, military miniatures, firearms and edged weapons (now in the Heritage Museum, Cape Cod), plus nautical models for good measure.

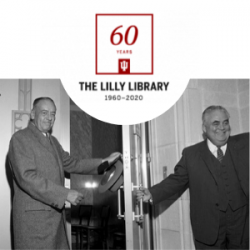

Between 1954 and 1957 he gave what was widely considered to be one of the finest private libraries in the world to Indiana University - more than 20,000 books and 17,000 manuscripts plus 50 oil paintings and 300 prints. These formed the foundation of the rare book and manuscript collection of the Lilly Library. When J.K. Lilly and Herman B Wells opened the doors to the Lilly Library in October 1960, it already held about 100,000 printed books and nearly 1,000,000 manuscripts, representing decades of Indiana University's effort toward establishing itself as one of America’s vanguard research institutions. Today, the collections have grown to more than 450,000 rare books and 8.5 million manuscripts.

As he had envisioned, these printed books and manuscripts had a transformative effect on the intellectual life of the University, and in turn, the state of Indiana. President Wells had immediately recognized the collection’s profound significance and determined that a freestanding library was required to not only care for the materials, but to establish and proclaim IU’s position as caretakers and curators of the state’s most valuable literary possession.

Josiah Lilly's range of interests, and the extent to which he realised his collecting goals, were summed up succinctly by Frederick B. Adams Jr., at the dedication of the Lilly Library: ‘Mr Lilly's books cover so many fields that it is difficult to believe that any one man's enthusiasm could encompass them all. It is equally astounding that he was able to acquire so many books of such scarcity and quality in the short space of thirty years. Money alone isn't the answer; diligence, courage, and imagination were also essential. The famous books in English and American literature, the books most influential in American life, the great works in the history of science and ideas, all these are among the 20,000 Lilly books in this building.’

The Autumn issue 1957 of The Book Collector includes not only the Modern Collectors focus on Lilly, but other nuggets in News & Comment where the Lilly collection was ‘(probably not over-exuberantly) as the largest and most valuable benefaction of its kind ever made to an American university.’ Of A Edward Newton’s ‘One Hundred Books Famous in English Literature (1903) the Lilly had eighty-seven, ‘which can be considered pretty good going for a private collector in the course of twenty-five years’. Exactly the same percentage held true of his holdings of the Grolier Club's One Hundred Influential American Books Printed before 1900 (1947).

The first book Lilly remembered - it was read aloud to him by his mother - was The Swiss Family Robinson, represented in the library by its first appearance in magazine form.

The Wall Street crash meant that Lilly bought some ‘...very nice books from the latter part of the Kern sale.’ But it also resulted in him seldom bidding ‘...at auction from that time on and when he did, even when angling for such items as The Bay Psalm Book, he never gave an unlimited bid. As a collector he may have learned the hard way, but he learned fast and the lesson stuck.’

In our Spring 1961 issue Randall wrote about Lilly, that ‘he wanted his favourite books, wherever possible, to be in their original state, wrappers, uncut, as issued, or, failing this, in a harmonious contemporary binding, and would have no truck with fine bindings for their own sake.’

In the Summer 1966 issue we reported that ‘Mr David Randall's appointment as its [the Lilly’s] custodian was exactly right, for not only had he and his former colleague at Scribner, John Carter, had a considerable hand in the formation of the Lilly Library, but the records indicated that in his care the Library would add an important posting station to the itinerary of scholars.’ A lovely memory of Carter appeared in our obituary of him in Summer 1975: ‘you never saw John at a loss for words or put out by any cross or misadventure. (Except once: at the inauguration of the Lilly Library at Bloomington, the celebrations included a full-throated contralto who sang a hymn to the benefactor beginning, “Lilly, you're the flower of the campus, with your Gutenberg Bible...”, at which point John's eyeglass fell into his soup.’

In our special Ian Fleming issue in Spring 2017, Joel Silver, the Lilly Library's director, wrote an article on ‘Books that had started something’ about Ian's collection. In it he quotes Carter's correspondence with Muir:

The books finally arrived at the Lilly Library in October 1970, almost six years after probate had been granted to Fleming’s executors. On 23 October Randall wrote to [Percy] Muir: well, Fleming is in and checked. There are five missing items – all minor . . . but nothing to make any fuss about. Looking it all over I’m very pleased to have it and I am looking forward to great fun in doing the exhibition and catalogue – probably sometime next spring. It must have been a lot of fun for you getting this together – it should be called the Muir collection, actually. I suspect Ian never saw a book once it was in a case. And by the way, though it frustrated you at the time, it’s a good thing they were in cases or mildew could have ruined a lot of them. In a way it’s a shame Ian didn’t get better copies of some of the books, as he easily could have at that time. The condition on some of the works is absolutely dazzling but others (often less rare) could be improved. But I know collectors and their reactions. One of Lilly’s great virtues was his absolute strictness on condition but he was a true collector.

The Lilly Library is currently closed for refurbishment through to June 2021, but we expect some outstanding exhibitions taking place then, if those mentioned in our Winter 2010 issue to celebrate the 50th anniversary are anything to go by:

‘Treasures of the Lilly Library’, curated by Joel Silver and Cherry-Williams; ‘Of Cabbages and Kings’, looked at some of the Lilly's ‘Unexpected Treasures’ ranging from royal documents to cartoon art and comic books, sheet music and pop-up books; and ‘Gilding the Lilly: One Hundred Medieval Manuscripts at the Lilly Library’ co-curated by Christopher de Hamel and Cherry Williams.

Our Archive is always here if you want to explore and find more about these great figures from the past, Josiah Lilly, Ian Fleming and David Randall.

3 October 1960. J. K. Lilly and Herman B Wells opening door to the newly-dedicated Lilly Library. Image number P0056007. Indiana University Archives.