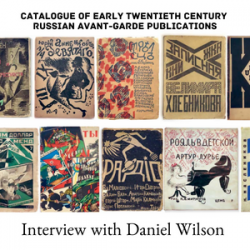

"A Catalogue of Early Twentieth Century Russian Avant-Garde Publications" is the latest printed catalogue by Marcus Campbell Art Books.

We asked Daniel Wilson, graphic designer and researcher for this catalogue, a few questions about the highlights, background of the collection and his approach to cataloguing.

You don't usually produce hard copy catalogues, what motivated you to have this one printed?

Modern art books tend to sell themselves, at least, I think so. This seems to be the case in a bricks-and-mortar shop like Marcus Campbell Art Books, which has a wide well-populated window bay facing the Tate Modern. But every so often a cache of rare or significant volumes require something more substantial in the way of presentation.

The costs of colour printing are high, so a stock-list needs to be special to justify the production of a hard copy catalogue. Marcus is always bringing interesting collections into the shop, but on this occasion he had acquired something larger with an inbuilt coherence, thanks to its diligent owner, a scholar in the field of Russian art, Christina Lodder. For most booksellers, dealing with a collection such as this one is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Marcus had noted whilst examining these books - most of which seldom appear on the market, normally only found in museum display cabinets - that their strong visual impact and rarity hinted at the idea of showcasing them in print. Immediately apparent was the advanced state of book graphic design in early 20th century Russia, so it felt bibliophilically logical to make a tactile catalogue drawing upon this.

Daniel, how did you get involved in this project?

I was enlisted as the designer for the catalogue at the suggestion of William English - a long-time employee at Marcus Campbell's, and specialist in avant-garde art. I had previously been the designer on an unusual artist's book for William English ('Perfect Binding: Made in Leicester' published in 2020). We occasionally worked on this at the bookshop during downtime, for the convenience of the shop's space and its ambient lighting. This project similarly involved the presentation of unique archival material in a clear, visually pleasing way. The writer Paul Gorman had later described the book as being "adventurously presented", and so I was engaged to apply this adventurousness to the Russian catalogue... However, the antiquarian Russian items already had so much visual adventurousness going for them - all those striking angles and manipulations. There's something about the Cyrillic alphabet that lends itself to visual experimentation.

The collection was assembled by Christina Lodder, president of the Malevich Society in New York, can you tell us a little more about her and how she started her collection?

Christina Lodder is a world-renowned expert in Russian modernism, authoring the English-language bible of Russian Constructivism in 1983 (a book which is regularly asked for in the bookshop) and actively contributing to many other key texts in this field. Christina's work has also raised the profiles of artists such as Natalia Goncharova and Naum Gabo in the west. Christina accumulated her collection over quite a few decades, drawing upon on it for her research. Much of it was apparently obtained during frequent stays in Russia, and sometimes items were gifted to her.

How did you go about working together on this catalogue?

Christina Lodder was quite hands-off, as she was busy with other things. Christina had supplied Marcus with a rough list of the book titles in Romanised Russian (there are actually a few German and French items too). I don't read Russian, but had previously designed a Russian typeface and had some familiarity with the phonetics, so I correlated the titles to the correct book and rearranged them alphabetically by author. My Russian-speaking friend, Ilia Rogachevski, also helped translate two of the ink inscriptions. Every week Marcus brought another box to the shop, where I'd photograph the contents. Photographing the items seemed preferable to flatbed scanning, which often doesn't reflect the condition adequately.

One useful feature seen in these Russian books - rarely seen in the west - is that the publishers state the edition size on the colophon. This helps with identifying editions, and of course online library databases are an invaluable tool. Condition assessment and pricing was carried out by Marcus Campbell and William English.

We had looked at the classic 1977 'Ex Libris' bookseller's catalogue 'Constructivism & Futurism: Russian & Other' which was so rigorous and extensive that it's still used today as a bibliographic resource in the same way E.F. Bleiler's sci-fi bibliography is used as a go-to sourcebook for sci-fi booksellers. We over-optimistically hoped to produce something of similar permanence, although after seeing the Ex Libris catalogue I felt so daunted by the level of scholarship for each entry. But in practice, with our catalogue, detailed deeply-researched descriptions were only really required to unknot what booksellers might refer to as the 'sleepers': the mysterious and "not in Copac or OCLC" titles with seldom-told backstories, for instance, the 1920 INKhUK manifesto charter (#40 in the catalogue).

Could you tell us about some of the key names of the Russian Avant-Garde movement?

Played out within the Christine Lodder collection is the role of Italian Futurism in catalysing modernist activity in Russia (via Genrikh Tasteven's translated texts for Russian readers, Nikolai Radlov's Futurist theory text, etc.). Futurism took on new forms in Russia, splitting into distinct branches, e.g. Cubo-Futurism and Rayonism, but also led to reappraisals of ancient Russian folk art (which Italians would've regarded as very un-Futurist!). There was an explosion of both literary and artistic modernism, and these often combine within anthologies such as 'Futuristy' (1914) [The First Journal of the Russian Futurists] edited by Kandinsky.

Visual artists and writers have a co-dependency, which is apparent in this collection. Writers like Nikolay Punin, Ilya Ehrenburg or Marietta Shaginyan had their publications adorned with modernist artwork by figures such as Vladimir Lebedev, Kazimir Malevich or Aleksandr Rodchenko. Writer-theorists were also instrumental in attempts to reconcile art movements with the volatile politics of the period. But there were many versatile figures such as Vladimir Mayakovsky, Natalia Goncharova, Aleksei Kruchyonykh, and Elena Guro, who worked in multiple fields, including printmaking, painting, music, poetry, stagecraft, theatre, etc. Vladimir Tatlin was also a notable artist. Tatlin had architectural plans for a giant monument to surpass France's Eiffel Tower as a symbol of modernity, to be built in St. Petersburg. Tatlin's tower never came to fruition. This illustrates a sense you get from the artworks of forward-looking movements of the past: a sense of parallel realities - of what could have been.

Did you discover any long forgotten names of the movement?

Yes, there were some 'sleepers'. One that particularly appeals to me personally is #29 in the catalogue: Grigory Gidoni's self-published 1930 'The Art of Light and Colour'. Continuing on the theme of parallel realities - the field of so-called 'colour art' is a cultural cul-de-sac that was made obsolescent by colour cinema, and its techniques were absorbed into theatre lighting. For a brief time colour light-shows were regarded as a standalone artform, prompting strange new inventions. Aside from possessing all the rough-hewn quirks of being self-published, Gidoni's treatise outlines his idiosyncratic theory of colour art as analogous to music, and it has escaped the notice of western scholars, being absent from Adrian Bernard Klein's final 1937 edition of 'Coloured Light: An Art Medium' published in London.

Another interesting area within the collection is Russian children's books with modernist illustration. This is a relatively under-researched area. Nadezhda Lyubavina is one such illustrator who deserves attention, along with the movement she was involved in, 'Soyuz Molodezhi' aka 'Union of Youth'. We listed issues two and three of the extremely rare anthologies this group produced between 1912-13 (#111) - very ahead of their time.

What would you suggest to someone wanting to start a collection in this field? Which are key pieces any new collector should try and add to their collection?

Buy what you personally like. As general advice: grab new catalogues (digital or otherwise) as quickly as possible because things sell fast, usually to other bookdealers and colleagues in the trade. This is great for the bookseller of course, but, not being a bookdealer myself, it seems dealers have a sixth sense for what is collectable, swooping in gannet-like, and so it can be difficult for the more impecunious collector. Having said that, the market is driven by collectors and it only takes the enthusiasm of one collector to influence its behaviour, even if this enthusiast's interests lie in areas currently overlooked.

I find the Russian Futurist's interest in folk art most intriguing, and a possible basis for a collection; items such as the exhibition booklet for 'The Art of the Peoples of Siberia' (1930) [#105], or the lavish leather-bound 'Exhibition of Ancient Russian Art' (1913) [#127] might form a bedrock of such a collection. If a collector is more interested in making an investment, significant texts not yet translated into English are worth considering - there are plenty in the Lodder collection that would benefit from an English-language republication (I understand early texts on Russian cinema are undergoing reappraisal by academics at the moment).

Many thanks to Daniel for providing insight into the creation of this fascinating catalogue.